In the 1930's my grandfather, Andrew Dreger, Sr., built a large four-sided street clock that displayed the time, day, date, month and phase of the moon as well as the solar times in several large cities around the world.

It first stood near the sidewalk on East Anaheim Street in Long Beach, California beside the two-story apartment house he had built almost 20 years earlier. Imposing in size, the faces were about three feet across, and it stood at least 15 feet tall. It kept the hours silently on its tall pedestal not far from the busy roadway where traffic kicked up street dust.

The housing and pedestal column were originally a dull silver color with a darker accent framing each face. Brass balls and small lion head ornaments decorated the corners of each side. Laurel branch adornments separated spaces at the upper corners between the sides, and a crowning sunburst finial topped the crest of each side. In back of the clear glass faces, dials were marked by Roman numerals on frosted panes. When the light was right, faint shadows of the mysterious inner workings could be seen. Driven by a small electric motor, 19 separate dials were synchronized to work together. It had no chimes or bells and made no ticking sounds as a pendulum driven or spring wound clockwork would have.

Though silent, it attracted attention with its size and elegant form. Passersby would tilt their heads skyward to study it. Some made a daily ritual of pulling out pocket watches to check their accuracy. We could hear voices from inside the house as people commented to one another about what time it was in places where cousins or aunts lived in Berlin or Petrograd.

Grandpa climbed his ladder each morning to polish the three large clock faces. He opened the door on the fourth side to inspect the inner workings and to make any adjustments. When he climbed back down, he would look up one more time to recheck the settings against his own gold pocket watch, then slip his small timepiece back into his vest, so only the gold chain showed.

Lantana bushes, with their tiny colorful bouquets, grew in narrow planters at the front of the apartment house. When their flower heads developed clusters of small round berries, neighborhood boys on their way to school, would pick the fruit and throw the little balls at a clock face target leaving purplish-black stains on the glass. Grandpa did not find this amusing. It is probably good that my sister and I did not understand his German expletives when he discovered evidence of this youthful "target practice". The lantanas were replaced with geraniums and jade plants.

THE APARTMENT HOUSE ON E. ANAHEIM ST

When the house was built in about 1914 there were no other structures nearby, as shown by some old family photos. Andrew Dreger had done most of the construction himself. He was a carpenter and builder as well as a mechanic and repairman. Long Beach, at the time, was already becoming a seaside resort town with a wide stretch of sand, a boardwalk-style amusement park, a saltwater bathhouse, a wooden roller coaster (predecessor to the famous Cyclone Racer) and a beautifully carved carousel.

The apartment, about a mile and a quarter from the seashore, was a two story wooden structure of no particular style. It was simply built; just a big box with clapboard sides. In some places the windows were of uneven size and placement. The lower front part of the building had first been rented out to a shopkeeper-- sort of a general store or grocery, while the upper floor was the Dreger residence. A constant series of remodeling and additions added to the eccentricity of the design.

By the time I remember it, in the 1940's, there were black wires strung on insulators and water pipes here and there on the exterior. The wires, pipes and the inconvenient bath and laundry rooms near the back stairway attested to the fact that the building had been constructed before such conveniences as home telephones, electric power and indoor plumbing were common. Sconces on the interior walls, showed where gaslights had once been connected. Long Beach, close to the Signal Hill and Wilmington oil fields, had natural gas hookups for lighting before residential electricity became available. It had gone through a series of different paint schemes, but in later years was an off-white color.

THE SAN DIEGO CLOCK

Grandpa knew about the Jessop Clock. It had won a gold medal at the 1907 California Stare Fair, and it still stands in San Diego. The form looks quite familiar. After that clock was installed in front of Jessop's Jewelry store in San Diego, Grandpa Dreger took a few trips south to specifically to see the item that undoubtedly inspired him to build his own version. One picture in our album shows the Dreger family on board the S.S. Yale passenger ship, which provided service from Wilmington to San Diego. In the photo, the family poses in their Sunday best on the ships deck in 1925. The photo shows Andrew Dreger, Sr. age 57, Martha Dreger, age 35, Lucile Dreger (my mom) age about 10, Andrew Dreger Jr. 4 or 5, and Andrew's daughter, Anna Dreger about 20.

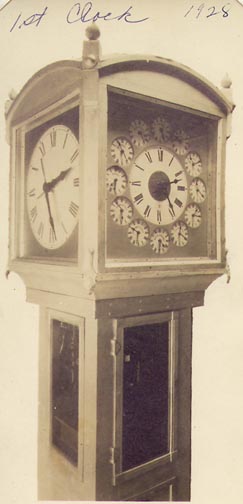

Andrew built a smaller version of his big clock in time to be exhibited

at the 1928 Pacific Southwest Exposition in Long Beach, an ambitious world's

fair-type celebration of international cultures, staged in a complex of

faux-Moorish castles near the ocean. We have an old photo of the early

clock that shows two of the faces-- one with the international dials.

It appears to be about seven feet tall in a square case.

Andrew built a smaller version of his big clock in time to be exhibited

at the 1928 Pacific Southwest Exposition in Long Beach, an ambitious world's

fair-type celebration of international cultures, staged in a complex of

faux-Moorish castles near the ocean. We have an old photo of the early

clock that shows two of the faces-- one with the international dials.

It appears to be about seven feet tall in a square case.

Many people have noted the similarities in appearance between

the Jessop Clock and the big Dreger clock. He certainly took notes and

made sketches, but the fabrication and workings of his clock were entirely

different. The international dials on both clocks reference a lot of the

same cities, but they are not exactly the same. Dreger's includes two

South American cities.

EARTHQUAKE

The apartment house, being a more forgiving wood framed construction, survived the March 10, 1933 Long Beach earthquake which brought down masonry and brick buildings all over the city, killing about 120 people and doing damages which, at the time, were estimated at 50 million dollars. The Dreger property became sort of a neighborhood soup kitchen at that time because grandma still had an old-fashioned wood stove which was moved out of the house and into a backyard tent where the family lived until the aftershocks of the following year subsided. Grandma had wanted a modern gas stove like most residences had by that time, but Andrew Dreger was a "thrifty" sort, and didn't think the modern convenience was necessary as long as the wood stove still worked. The gas lines, of course, had all been broken in the 6.5 tremor. Their house suffered only minor damage.

Family lore places the completion of the clock in 1933. It is not known

exactly how long after the earthquake, the clock was erected-- (or if

it even had been put up before the quake). I don't recall Mom mentioning

that specifically.

The construction of the Golden Gate Bridge was also begun in 1933. During the next four years Grandpa Dreger made several trips up the coast, probably booking passage on the S.S. Yale again, for visits to San Francisco to see the progress of the famous span.

DREGERS (taking the scenic route in) COMING TO AMERICA

Grandpa's family was German nationals living in a part of Russia, which

was once Poland, when he was born. If that is not confusing enough, his

father Gottlieb had the urge to travel from place to place throughout

his life. He had been to Turkey, as well as a lot of European countries.

Often, the whole family went on these trips. The family, which included

several other children, were all living in Versailles, France when they

got a letter from a Portuguese friend who told them about an opportunity

in Brazil. They all hopped on a slow ship that took several weeks to get

them to a Brazilian coffee plantation where they lived for six years.

Andrew, who was the oldest son, stayed in Rio de Janeiro (one of the cities

referenced on the clock face) and worked at a bicycle repair shop, instead

of going to the coffee growing region with the rest of the family. Possibly,

he got his early experience in basic mechanical skills there.

Grandpa's family was German nationals living in a part of Russia, which

was once Poland, when he was born. If that is not confusing enough, his

father Gottlieb had the urge to travel from place to place throughout

his life. He had been to Turkey, as well as a lot of European countries.

Often, the whole family went on these trips. The family, which included

several other children, were all living in Versailles, France when they

got a letter from a Portuguese friend who told them about an opportunity

in Brazil. They all hopped on a slow ship that took several weeks to get

them to a Brazilian coffee plantation where they lived for six years.

Andrew, who was the oldest son, stayed in Rio de Janeiro (one of the cities

referenced on the clock face) and worked at a bicycle repair shop, instead

of going to the coffee growing region with the rest of the family. Possibly,

he got his early experience in basic mechanical skills there.

Sometime in the mid to late 1880's, Andrew's father decided that they should all go to the USA. Since there was no direct passage to North America, they all sailed back to Europe and stayed in Belgium for a while. There was not enough money to book passage for the entire family, so Andrew stayed behind to work for a couple of years, then met up with his family who, by then, were living in Pennsylvania.

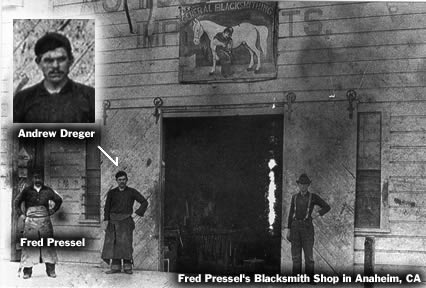

An old dim photo shows Andrew and coworkers posing in front of the F. Pressel blacksmith shop in Anaheim before 1910. He disliked horses-- perhaps due to his experiences in trying to shoe the critters when he worked as a blacksmith. That background plus his fascination with mechanical things probably contributed to his idea that 'horseless carriages' were the way to go.

BEFORE COMING TO CALIFORNIA

As a young man clearing land for a farm in Minnesota (

about 1900) , he saw a plume of smoke in the distance. When he reached

the cabin, his wife and baby were dead in the burned ruins.

By that time his parents, along with at least one sister and

two brothers had all moved on to California. Another wife died

in childbirth, a third gave him a daughter, but also died.

The fourth spent most of his money, mistreated his child and

they divorced. My grandmother was his fifth wife. He had not

had an easy life and lost wives and children in a series of

tragedies before marrying Martha Zellmer in 1912. She was twenty-two

years younger than he. They had children, at least three of

whom died, but my mom, Lucile, my uncle Andrew, Jr. and Anna,

his older daughter from his third wife, survived and had families.

Andrew's parents lived in Long Beach for a time. His sister, Emily Dreger Holder, may have helped to look after them in their later years, as their death records say they died in Buena Park where the Holders lived. They are buried in the old Anaheim Cemetery.

Andrew Sr. played the violin, though I'm told that his occasional practice of the instrument did little to improve his musical skills. My sister said he was somewhat better with the ocarina and harmonica, with which he could produce recognizable melodies that were mostly German songs that he knew from earlier days.

So even if musical performance was not his greatest talent, he at least had an appreciation and understanding of musical arts. Perhaps his interest in machines-- especially the rhythmic perfection of a precisely crafted pocket watch or mantel clock, had something to do with his musical sensibility.

There are lots of other little stories about him. Talented, he was perhaps, born a little before his time for the talents he had. He was inventive, inscrutable, dignified and bit cantankerous and impatient-- he was not a tall man, but quite handsome, especially in his younger years. His thick head of hair and neat mustache had turned a dark gray with a somewhat unruly disposition by the time I knew him. He was 75 years old when I was born.

Among some of his fascinating possessions was a hand cranked Victrola gramophone phonograph record player with a flared horn on the top, and a set of operatic recordings (thick 78 rpm) of Enrico Caruso and other classical music. He built a little cabinet 16x16" square with eight drawers down the front that were each about an inch and a half deep. It was sized so the phonograph player fit on top with narrow wooden rails on three sides to keep the music machine from sliding off. The shallow drawers were to store his record collection. It is beautifully built, sturdy and with all of the drawers sliding perfectly, and my mom later used it for thread and sewing notions, since it fit comfortably alongside her sewing machine.

WHEN I LIVED THERE

Grandma Dreger died when I was less than two years old. She was a little over 50. My sister remembers her, and everyone who knew her said she was practical, hardworking and kind. I never heard anything negative said about her. After another year or so, Mom knew that she needed to look after her father who was by then, almost 78 years old. She also knew she could not convince him to move away from all his "stuff" including the giant clock, so my parents sold our little house. My mom, dad, sister and I moved into the lower front apartment on Anaheim Street and Grandpa lived in the shop converted to living quarters in the back. He usually had dinner with us, but mostly kept to himself, busy with one project or another. There were renters in two small upper units and another in downstairs rooms in the rear.

Somehow I knew that I was not to bother Grandpa, who was always busy in his workshop, watch bench or cellar. All of those places were "off limits" to my older sister and me.

I did get to go down into the cellar a couple of times. It was like entering a haunted mine shaft with clay walls and timber supports. Muted light came from a couple of bare electric bulbs hanging from wires. Dusty jars of pickles and vegetables filled shelves dug into the hard-packed earth. Pieces and parts of clocks, radios, music boxes, plumbing valves, musical instruments and mysterious machines and mechanisms filled shelves and workbenches in a disorganized jumble. Gears, springs, bolts, screws and rivets filled jars and tin boxes. Rolls of wire and balls of twine were tucked into corners with lengths of pipe and metal bars. Tools hanging on the walls haphazardly framed portraits of kings, queens and European nobles from cigar-box advertising and magazines. In the dim light, the royals seemed to be watching over this doubtful treasure trove of mechanical hardware. Everything seemed to be held together by cobwebs.

There were garages and workshops in back of the house. Part of this area was later converted to living quarters as well. Near the back fence a corrugated tin covered a storage area with scraps of lumber, pipe and metal. Fig trees grew here and also sheltered the tin shed that had more tools, welding torches, soldering irons, anvils, lathes, a cobbler's bench and a small wood stove. He did much of his work here; the cellar was more of a storage space.

In the front corner of the apartment house was a small room, with a window that looked out toward the big clock. This was his watch repair area, a clean well-lighted workspace for delicate work.

MOVING OF THE CLOCK

After he passed away in 1952, my mom tried to donate the clock to the

city, hoping they would put his name on it and maintain it so it could

be continue admired and enjoyed by the public. Mom never tried to sell

the clock, she wanted to donate it and have it preserved. She was a little

puzzled that no one seemed to want it. Failing to find someone who would

accept it as a gift, the property was sold with the clock still in place.

Shortly after the sale, it disappeared from sight, leaving only the concrete

base that had held it in place. No one seemed to know where it was. About

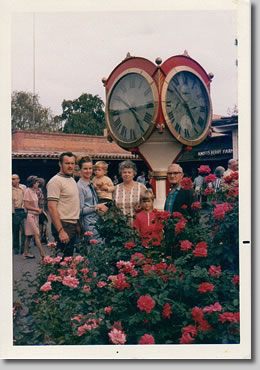

a year later, someone discovered that the clock was at Knott's Berry Farm

in Buena Park. It had been painted white with a bright red trim, and placed

on a much shorter pedestal than it originally had, the side without dials

had a round four-part painting depicting the yearly seasons added to it.

Though it looking somewhat different in its new surroundings, it was still

unmistakably recognizable.

After he passed away in 1952, my mom tried to donate the clock to the

city, hoping they would put his name on it and maintain it so it could

be continue admired and enjoyed by the public. Mom never tried to sell

the clock, she wanted to donate it and have it preserved. She was a little

puzzled that no one seemed to want it. Failing to find someone who would

accept it as a gift, the property was sold with the clock still in place.

Shortly after the sale, it disappeared from sight, leaving only the concrete

base that had held it in place. No one seemed to know where it was. About

a year later, someone discovered that the clock was at Knott's Berry Farm

in Buena Park. It had been painted white with a bright red trim, and placed

on a much shorter pedestal than it originally had, the side without dials

had a round four-part painting depicting the yearly seasons added to it.

Though it looking somewhat different in its new surroundings, it was still

unmistakably recognizable.

My mother, Andrew Dreger's daughter, contacted Walter Knott and got a letter back (in 1955) saying he would be happy to put her father's name on a sign with the clock. He also asked for a brief history. I still have the letter. I believe my uncle, Andrew Dreger, Jr. also went to speak to people at Knott's Berry Farm in person. For a while, a small sign with a notation about the clock being "made by A. Dreger", was placed in the rose garden, but one that only described the maker as a “fine German watchmaker” soon replaced that sign.

It stood in a quiet corner of rose garden in front of the Knott's Steak House Restaurant, near the "back entrance" to Ghost Town. The clock remained in the little garden, surrounded by a low picket fence, for several years and was eventually repainted with a more suitable and elegant color scheme of dark green with gold accents.

When it disappeared from the garden, we were disappointed for a while

but it later reappeared with Knott's graphic logos added, in front of

their new main ticket booth at the entrance where it drew the notice of

even more visitors. It was at Knott's for a total of about 50 years.

The Knott family actually had a neighborly connection with the Dregers. Andrew Dreger, Sr.'s sister, Emily Dreger Holder, and her husband David Holder had an nearby family farm where they raised chickens. The Knott family also employed Emily Holder for a time.

In August 2007, my son noticed that that clock was no longer in the front plaza. He did a search of the Internet and found it on an eBay listing! The description mentioned the maker only as being an "eccentric Clock Builder".

In one sense, my mom's wish was granted. At least during her lifetime, the clock was preserved and displayed in a place where thousands of people admired it. She was disappointed that her father's name was never permanently put on it. Mom died almost ten years ago.

If there is a chance that a little bit of the past can be brought back, we would be very satisfied to see the Dreger Clock displayed with its history. My grandfather might not have cared about the personal recognition, but it was at least something he was passionate about, and I think he also would have been pleased to know that someone cared enough about his work, to preserve it.

Rochelle Frank

granddaughter of Andrew Dreger, Sr.

19 Sept.

2007